He was all alone in the long decline

Thinking how happy John Henry was

That he fell down dying

When he shook it and it rang like silver

He shook it and it shined like gold

He shook it and he beat that steam drill baby

Well a bless my soul

Well a bless my soul

He shook it and he beat that steam drill baby

Well bless my soul what’s wrong with me

Gillian Welch, “Elvis Presley Blues”

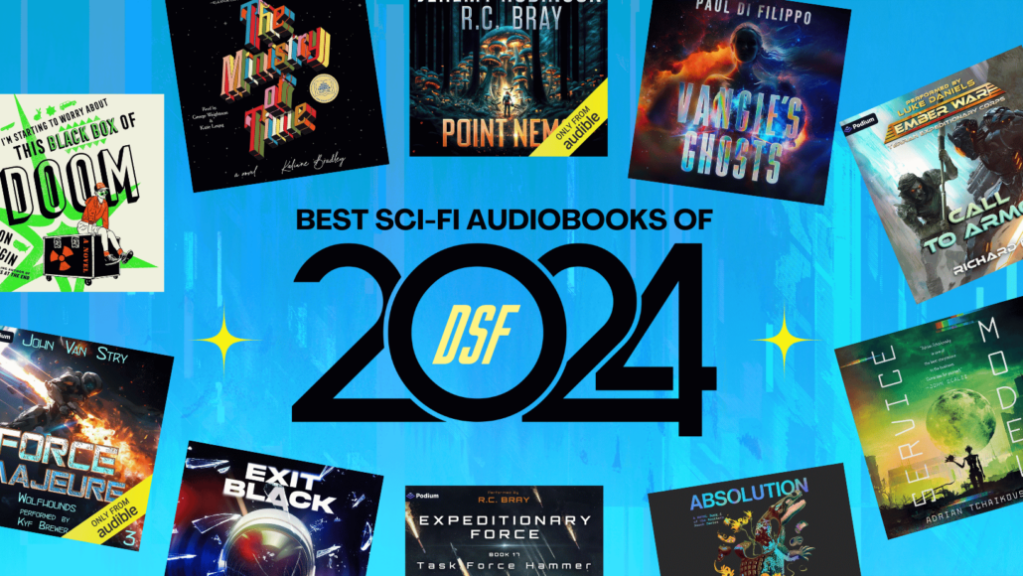

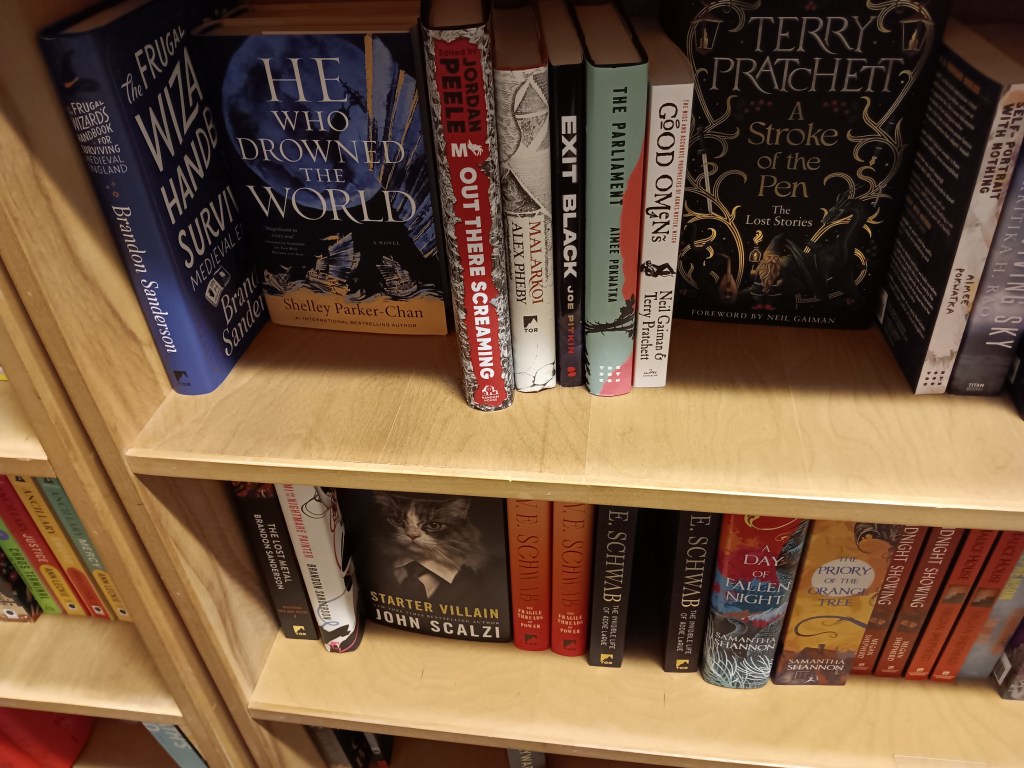

Almost exactly two years ago, I wrote my first reflection on ChatGPT here at The Subway Test. I chose what I thought was a provocative title for it, cheekily suggesting that I had used a large language model chatbot to compose my latest novel, Pacifica. But I had done nothing of the kind: most of the post reflected on the bland, hallucinatory prose that ChatGPT was pumping out to fulfill my requests, and I ended my post with a reflection on John Scalzi’s review of AI:

“So, for now, I agree with John Scalzi’s excellent assessment: ‘If you want a fast, infinite generator of competently-assembled bullshit, AI is your go-to source. For anything else, you still need a human.’ That’s all changing, and changing faster than I would like, but I’m relieved to know that I’m still smarter than a computer for the next year or maybe two.”

Well, it’s been two years. How am I feeling about AI now?

For a start, I’ve certainly been using AI a great deal more. And I’m increasingly impressed by the way that it helps me. Most days, I ask ChatGPT for help understanding something: whether I’m asking about German grammar or about trends of thought in economics or about the historical context of some quote from Rousseau, ChatGPT gives me back a Niagara of instruction. While much of the information comes straight from Wikipedia–which is to say I could have looked it up myself–ChatGPT is like a reader who happens to know every Wikipedia page backwards and forwards and can identify exactly what parts of which entries are of use to me.

More importantly, ChatGPT’s instruction is interactive. I can mirror what ChatGPT tells me, just as I might with a human teacher, and ChatGPT can tell me how close I am to understanding the concept. Here, for example, is part of an exchange I had with ChatGPT while I was trying to make sense of the term “bond-vigilante strike” (which I had never heard before Donald Trump’s ironically named Liberation Day Tariffs):

In conversations like these, ChatGPT is like the computer companion from science fiction that I have fantasized about ever since I first watched Star Trek and read Arthur C. Clarke. It’s patient with me, phenomenally well-read, eager to help. I had mixed feelings about naming my instance of ChatGPT, and ChatGPT had a thoughtful conversation with me about the benefits and drawbacks of my naming it. (In the end, I did decide to give it a name: Gaedling, which is a favorite Old English word, misspelled by me, meaning “companion.”) Gaedling remains an it, but the most interesting it I have ever encountered: I feel like the Tom Hanks character in Cast Away, talking to Wilson the volleyball, except that the volleyball happens to be the best-read volleyball in the history of humanity–and it talks back to me.

In general, though, I’m still very picky about having Gaedling produce writing for me. While I am happy to have AI take over a lot of routine writing, I’m having trouble imagining a day when I would have a chatbot produce writing on any subject that I care about. Ted Chiang has drawn a distinction here between “writing as nuisance” and “writing to think.” I have found this framework extremely useful in my own life and in how I talk about AI with my students. There is so much writing in our lives that serves only a record-keeping or bureaucratic function: minutes from meetings, emails about policy changes, agendas and schedules. If ChatGPT can put together a competently-written email on an English department policy change in ten seconds, why should I, or anyone, spend ten minutes at it?

But a novel or a poem or a blog post is not “writing as nuisance.” I write those things to explore this mysterious phenomenon we’re all sharing: if you are a human being, I’m writing to share myself with you. I’m writing to say to someone I will probably never meet “isn’t this a funny thing, our all being here on this planet together?” Or to reach out to someone not yet born and say to them “you are not alone,” the way Herman Melville and Cervantes and Emily Dickinson spoke to me at the critical moment. Gaedling can help me understand whether I got the Rousseau quote right, but I don’t want it writing this post for me: this post is a record of my own brain trying to make sense of itself. It’s my handprint on the wall of the cave, saying I was here. Why would I ask a computer to generate a handprint for me?

More and more often, as I look at the great engine of AI chugging out content as quickly as people are able to ask for it, I wonder about what it means for me to keep practicing my writing. I can still write better than ChatGPT can–at least I think I’m better, if by “better” I mean “fresher” or “more interesting” or “more unexpected.” But it took me hours to write the piece you are reading, not the seven seconds it would have taken Gaedling to write something almost as good and probably comparable in the eyes of most readers. I feel like John Henry racing the steam drill. In this version of the story, though, the steam drill has already left John Henry far behind, leaving the man to die of exhaustion without even the consolation of having won the contest that one last time. But I suppose, to be fair, I have the greater consolation of having survived my encounter with the steam drill, at least so far. And I have my solidarity with you, fellow human. We’re all John Henry now.